Identifying the most common causes of gastro infections in laboratory and academic environments is critical to improving public health. Professionals in laboratory and educational settings perform in-depth research on gastrointestinal (GI) infection etiology.

Gastroenteritis is an inflammation of the gastrointestinal system brought on by various pathogens. The types of germs causing infections depend on factors such as economic development, geographic region, hygienic standards, and sanitation levels. Additionally, infections can be distinguished as community-acquired or hospital-acquired, with the latter posing higher risks due to antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

The prevalent etiology of gastrointestinal infections includes viruses, bacteria, parasites, and fungi. These are categorized based on their microbial origin, each presenting distinct challenges for diagnosis and treatment.

For instance, bacterial infections often arise from contaminated food or water, while viruses such as Norovirus spread through person-to-person contact. Parasites like Giardia lamblia may be transmitted through contaminated water sources. Candida spp., a fungal agent, can result in gastrointestinal infections, particularly in immunocompromised individuals.

Comprehending these origins advances our knowledge and reaffirms healthcare professionals’ crucial function in protecting public health through accurate diagnosis and treatment of GI tract illnesses.

1. Viral Causes

Several viral agents are associated with gastrointestinal infections. Each viral agent has distinct features in structure, transmission modes, and impact on affected individuals.

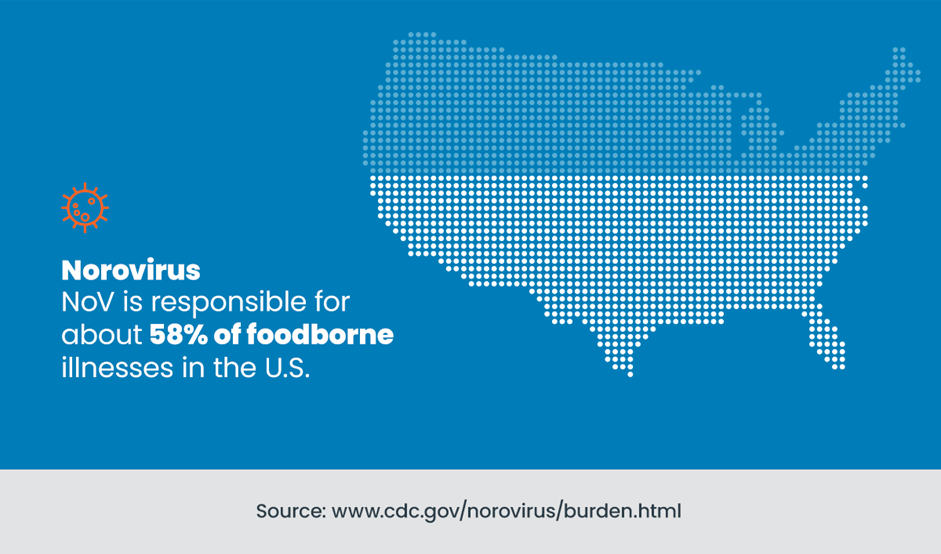

Norovirus

Norovirus (NoV) — previously known as the Norwalk-like virus — is small, non-enveloped, and highly contagious. While there are several genogroups of NoV, only genogroups I and II are responsible for most human cases.

Norovirus is one of the predominant etiological agents responsible for GI illnesses, accounting for an estimated 21 million cases in the U.S. annually. Its primary modes of transmission include contaminated food, water, surfaces, or infected individuals. NoV is responsible for about 58% of foodborne illnesses in the U.S.

Norovirus manifests with persistent diarrhea and prolonged viral shedding, particularly in immunocompromised individuals. Its prevalence is noteworthy for leading to occasional cases and outbreaks that significantly impact specific settings. Some prevalent Norovirus settings include restaurants, catered events, schools, childcare centers and health care facilities.

Rotavirus

Rotavirus (RV) — named after its wheel-like appearance — is a segmented, double-stranded RNA virus. It is the predominant etiological agent responsible for acute gastroenteritis in children worldwide. Even with the advent of vaccines, RV continues to be a widespread viral agent worldwide.

There are now ten distinct rotavirus species recognized (A-J). While species B and C rotaviruses also result in a lower but significant percentage of infections worldwide, species A rotaviruses are the most prevalent etiology of infections in children.

Rotavirus transmission occurs when one touches virus-contaminated surfaces, objects, or food and subsequently puts unwashed hands in one’s mouth. Globally, the prevalence of infection is similar, but the likelihood of a deadly illness is higher in low-income areas.

Rotavirus is prevalently considered a winter illness, particularly in the world’s more temperate regions. Infections typically occur year-round in tropical areas, where the seasonal tendency is less noticeable.

Rotavirus infections often result in prolonged gastroenteritis and dehydration, which is particularly impactful in pediatric populations.

Adenovirus

Adenovirus (AdV) is a DNA virus prevalently found in humans and animals, often affecting adults and children. Adenoviruses come in over 100 serologically distinct varieties — 49 of which can infect humans.

AdV infections — while usually causing self-limited GI disease in immunocompetent individuals — take a more severe course in specific settings.

Bone marrow transplant patients and solid-organ transplant recipients — especially small bowel transplant recipients — may experience gastroenteritis and hemorrhagic colitis due to AdV. This emphasizes the virus’s capacity to result in severe disseminated disease in compromised hosts.

Adenovirus transmission usually occurs via respiratory droplets, but the oral-fecal route is also prevalent. AdV infections are frequent in medical facilities, childcare centers, closed or congested areas like military barracks, public swimming pools, and households with small children.

Astroviruses

Astroviruses (AstVs) — characterized by their icosahedral cubic capsids — contribute to up to 9% of nonbacterial gastroenteritis in pediatric populations globally.

AstVs are primarily transmitted through the fecal-oral route, prevalently through contaminated food, water, and fomites. The ingestion of these contaminated substances introduces the virus into the GI tract, leading to infection.

AstVs exhibit a higher prevalence in settings with young children — especially those under the age of 2 — where symptomatic illness is most prevalent. Additionally, immunocompromised individuals and elderly populations are susceptible.

Escherichia Coli

Escherichia coli (E. coli) — particularly the pathogenic strains like E. coli O157:H7 — has diverse habitats. In addition to being a component of commensal gut flora, E. coli is also found on hospital and long-term care facility floors. The most prevalent gram-negative bacterium in the human GI system, E. coli, is not pathogenic in this environment.

Humans and other animals can transmit diarrheagenic E. coli pathotypes through their excrement. Fecal-oral transmission, ingestion of contaminated food or drink, interpersonal contact, contact with animals or their surroundings, and swimming in untreated water are the other modes of transmission.

Clostridioides Difficile

Clostridiodies difficile, formerly known as Clostridium difficile (C. diff), — found in the environment and human intestines — poses a significant healthcare-associated infection risk. Although C. diff bacteria are frequently prevalent in the environment, most C. diff cases happen either during or after an antibiotic prescription.

This risk factor is due to the fact that antibiotics — which combat bacterial illnesses by eliminating pathogens — can also eradicate beneficial bacteria that shield the body from dangerous infections such as C. diff infection.

C. diff releases in excrement. Commodes, baths, and electronic rectal thermometers are examples of surfaces, objects, or materials that potentially harbor C. diff spores if they get contaminated with excrement.

3. Parasitic Causes

Multiple parasitic agents contribute to GI infections, each characterized by unique features related to their life cycle, transmission modes, and impacts on affected individuals.

Giardia Lamblia

Giardia lamblia (G. lamblia) — a flagellated protozoan — has a two-stage lifecycle involving cysts and trophozoites. In contaminated water, cysts transform into trophozoites in the small intestine, causing an infection.

G. lamblia can be found worldwide. Giardia infection is the most prevalent intestinal parasite disease in the U.S., affecting over 1 million individuals annually.

Contaminated water sources are the primary reservoirs for Giardia. Inadequately treated drinking water, recreational water, and food contaminated by infected individuals contribute to its transmission. There is minimal possibility that humans could contract Giardia from pets. Typically, people are not infected with the same strain of Giardia as dogs or cats are.

Outbreaks often occur in poor sanitation and water treatment areas. Campgrounds, daycare centers, and institutions with shared water sources are at heightened risk.

Cryptosporidium

Cryptosporidium (Crypto) — a coccidian protozoan — has a complex life cycle involving oocysts. Infection occurs when individuals ingest oocysts, which release sporozoites in the small intestine, causing the disease.

One way that Cryptosporidium spreads is through the fecal-oral pathway. Crypto is most adapted for spreading through polluted drinking or recreational water due to its low infectious dose, extended life in wet conditions, prolonged communicability, and excellent tolerance to chlorine.

Additionally, viral pathogens can spread by eating contaminated food, coming into touch with contaminated surfaces, or coming into contact with infected persons or animals.

Cryptosporidium outbreaks are linked to waterborne transmission, affecting communities with compromised water treatment systems. Daycare centers, health care facilities, and food handlers also face elevated risks.

Entamoeba Histolytica

Entamoeba histolytica (E. histolytica) — an amoebic protozoan — has a cyst-trophozoite life cycle. Transmission occurs when cysts are ingested, transforming into trophozoites in the colon and causing invasive disease.

Contaminated food and water are primary sources of E. histolytica. Poor sanitation, inadequate hygiene practices, and crowded living conditions contribute to transmission. E. histolytica can result in infected individuals developing Amebiasis.

Amebiasis is found worldwide. However, it is most prevalent in tropical regions with inadequate sanitation. Overcrowded areas, areas with insufficient waste disposal and regions with compromised water quality are at heightened risk. These regions also risk recent immigrants and refugees.

One prevalent diarrheal infection seen in returned travelers is E. histolytica. Travelers who stay longer than six months have a significantly higher chance of contracting E. histolytica infection than those who stay shorter than a month.

4. Fungal Causes

Numerous fungal agents are linked to GI infections, each characterized by unique structural attributes, transmission methods and effects for affected individuals.

Candida Spp.

Candida spp. — predominantly C. albicans — is a predominant etiological agent responsible for esophagitis in immunocompromised individuals. Patients undergoing radiotherapy or chemotherapy — especially for hematologic malignancies — are prone to oral candidiasis.

Candida spp. is prevalently transmitted through person-to-person contact, primarily via direct contact with infected individuals or their bodily fluids. Sexual transmission is a notable route, with Candida often present in the genital and oral regions. Additionally, vertical transmission from mother to newborn during childbirth is another recognized mode of Candida transmission.

Histoplasma Capsulatum

Histoplasma capsulatum, or GI Histoplasmosis, prevalently affects immunocompetent hosts, the risk escalates for patients with HIV, particularly in males. Those undergoing anti-TNF-α therapy or solid-organ transplants face an increased risk.

While GI involvement in AIDS patients with disseminated histoplasmosis is low, it can be fatal. Esophageal histoplasmosis may manifest with ulcers causing dysphagia or bleeding, predominantly affecting the colon and exhibiting high mortality rates.

Talaromyces Marneffei

Formally known as Penicillium marneffei, Talaromyces marneffei (T. marneffei) — a dimorphic fungus endemic in Southeast Asia — leads to uncommon cases of disseminated infection. This fungal agent impacts the GI tract in patients with HIV, renal transplantation, and corticosteroid therapeutic interventions.

Recent Research Advancements

Recent research has brought about notable advancements in the field of gastrointestinal infections. Here are some key areas of advancement.

Biosensors for Early Diagnosis

Studies explored biosensors development for the rapid and sensitive detection of viruses associated with gastroenteritis.

These biosensors leverage detection technologies — such as microfluidics and nanomaterials. These technologies detect viral pathogens in clinical samples with high specificity and sensitivity. Biosensors may improve patient health outcomes and help with timely public health interventions during outbreaks.

Vaccine Development

Advancements in vaccine technology have paved the way for developing novel vaccines against gastrointestinal pathogens, including RV, NoV, and enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC).

These vaccines use vaccine platforms — such as virus-like particles (VLPs) and live attenuated vaccines — to elicit immune responses against specific pathogens. Clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of these vaccines, offering hope for preventing GI infections in high-risk populations.

Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance

The emergence of antimicrobial resistance among gastrointestinal pathogens — such as Campylobacter and Salmonella — has prompted intensified surveillance efforts to monitor antimicrobial resistance patterns and identify resistance mechanisms.

Advances in molecular typing techniques, such as whole-genome sequencing (WGS), have enabled high-resolution surveillance of antimicrobial-resistant strains, promoting the implementation of targeted interventions to mitigate the spread of resistance.

Gut Microbiota Modulation

Recent studies have investigated the use of microbiota-based interventions — such as probiotics, prebiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) — to prevent and treat GI infections.

These interventions aim to restore gut microbiota balance, enhance mucosal barrier function, and modulate immune responses against pathogens. Clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of microbiota-based interventions have shown promising results.

Introducing The BioCode® Gastrointestinal Pathogen Panel

Our groundbreaking BioCode® Gastrointestinal Pathogen Panel offers a comprehensive solution, providing advanced tools for research and diagnosis in the medical industry.

Here are the key advantages of the BioCode® Gastrointestinal Pathogen Panel:

- Multiplex testing: Our panel’s multiplex testing capability allows the simultaneous detection of 17 gastrointestinal pathogens, including viruses, bacteria, and parasites — all in a single test.

- Reliable detection: With Barcoded Magnetic Beads (BMB) technology, the assay ensures reliable detection of specific microbial nucleic acids from symptomatic patients.

- Maximized sample throughput: Integrated with the BioCode® MDx-3000 system, our panel maximizes sample throughput without compromising quality, facilitating high-throughput molecular diagnostic testing in a cost-effective manner.

- Operational efficiency: Features such as data masking options and intuitive interfaces streamline workflows and support user-defined testing protocols.

- Compatibility: The panel’s compatibility with laboratory information systems (LIS) ensures seamless integration into existing laboratory workflows.

Transform Your Laboratory Experience with Applied BioCode

It is critical for professionals working in labs and academic environments to understand the many etiologies of gastrointestinal illnesses. To explore cutting-edge solutions for gastrointestinal infection diagnostics, consider partnering with Applied BioCode.

Our BioCode® Gastrointestinal Pathogen Panel — integrated with the BioCode® MDx-3000 system — empowers professionals with a high-throughput, multiplexed diagnostic approach. Detect and differentiate 17 pathogens — including viruses, bacteria, and parasites — from one sample, all in one test.

We encourage you to embrace the future of gastrointestinal diagnostics, and for inquiries or collaborations, contact Applied BioCode – where innovation meets precision in advancing gastrointestinal health outcomes.

Contact us online today for further inquiries.